A Buffered Environment

Are cats conscious? Good question, but one that this article doesn’t even touch—or does it?

The material below is from Self-Domestication and the Cultural Evolution of Language (PDF), as a chapter in The Oxford Handbook of Cultural Evolution. The article brings to mind a taken-for-granted intuition in education that schools and instruction represent ‘unnatural’ phenomena that we must begrudgingly live with, cloistering children away from the ‘real world’ (the most famous of this intuition playing itself out, surely, is the late Ken Robinson’s charge that schools kill creativity [and its incredible response]). The direct work that this intuition does is to throw good thinking away from teacher-centered, school-centered, and administrator-centered improvements (because that would just be more hideous unnaturalness) onto things like changing the arrangement of the desks.

So, here we are again, with more background evidence that another of education’s (widespread and policy-shaping) intuitions is bonkers, given that a natural ‘cloistering’ of human activity is likely what allowed for human social learning to become so powerful in the first place (bold emphases mine).

The HSD [human self-domestication] hypothesis, which is most notably articulated in Hare (2017), suggests that human evolution in the middle and late palaeolithic was characterized by selective pressures for less aggressive sexual and social partners. Out of the many factors that were suggested to trigger this selection for less aggressive behaviours in humans, the two most prominent explanations are (i) changes in our foraging ecology, whereas humans began relying on cooking as well as non-local food sources, entailing the need to move around and share resources with others . . . and (ii) climate deterioration and harsh environmental conditions during the last glaciation, which have increased the need for exchanging and/or sharing resources between groups. . . .

The HSD hypothesis suggests that our self-domestication may be responsible for many of the hallmark traits of humanity, and specifically for many of the traits that distinguish humans from Neanderthals (Theofanopoulou et al., 2017).

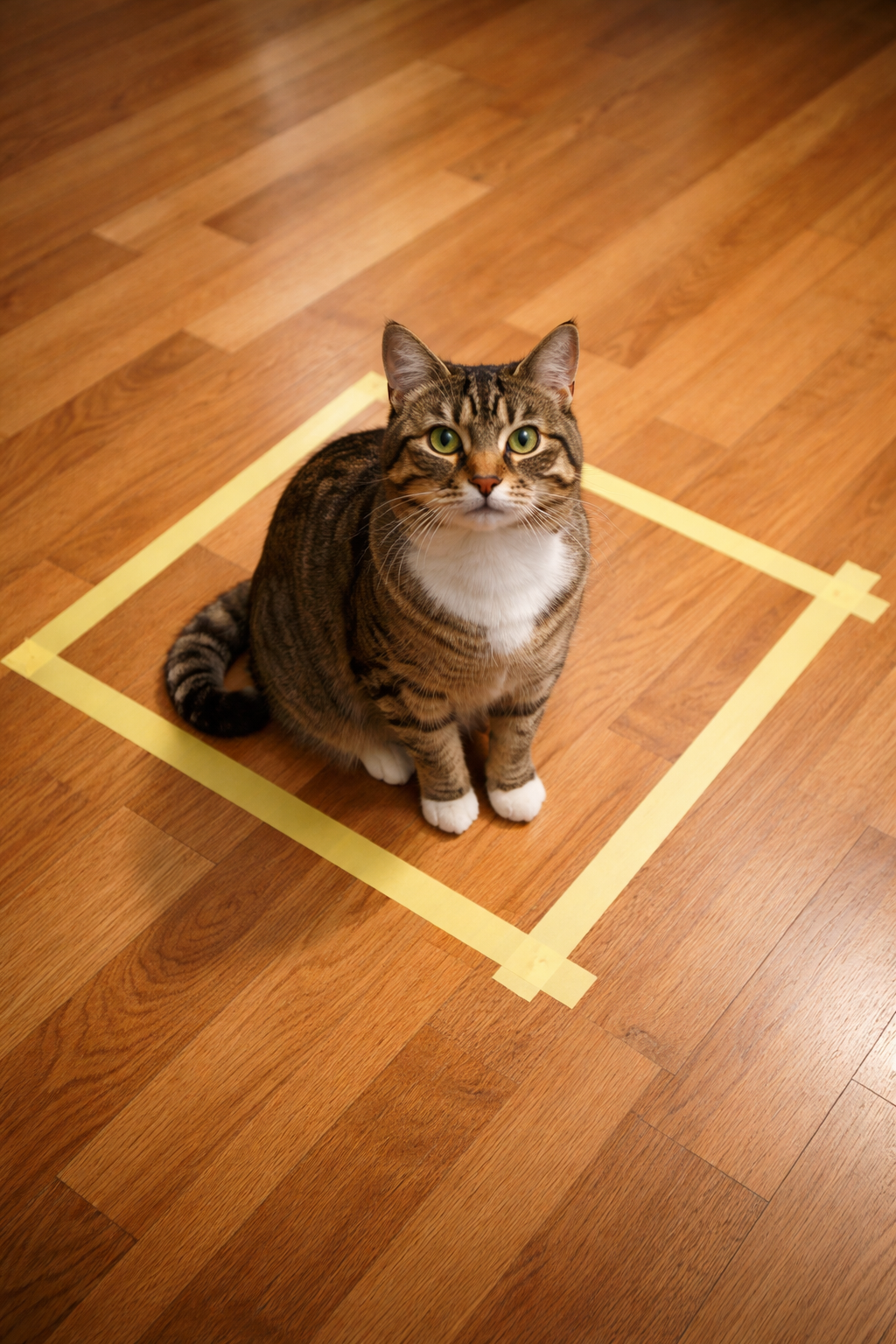

My own view on self-domestication (here and here) is compatible with this description, though it is centered more around the potential functions of human consciousness. While a changed ecology and climate were significant factors, triadic joint attention—a robust version of which I would call ‘social consciousness’—played a large role, in my thinking, in selecting for non-aggression, primarily because this automatic consciousness practically compelled communication. Triadic joint attention (social consciousness) generates its own ‘buffered social environment’—in the simplest case, a closed triangle of two individuals and an object of attention—which can then allow for the selection of communicative success (listener selection, the turn-taking and affect-inclusive transmission model, etc.), which involves all the different kinds of human communication (movement, voice, affect, representation, etc.).

A typical marker of (self-)domestication is a kind of buffered environment, characterized by reduced exposure to predators and other hazards and more consistent and reliable food supply. . . .

It is argued that HSD fuelled the processes and cognitive abilities that underlie the cultural evolution of language to begin with . . . and that it can help explain critical features of modern language such as pragmatics and turn-taking (Benitez-Burraco et al., 2021), grammar sophistication and innovation, child-directed speech, and even cross-linguistic variability.

This ‘buffered social environment’ provided for the evolution of more effective language use—communication became more compressible and informative*—which allowed everyone to better “infer the system of signals in their language, and also an ability to [better] infer the mental states and communicative intentions of other language users.” At a larger scale, the buffered environment becomes an extended period of juvenile development:

Another key outcome of domestication in a wide range of animals is an extended juvenile period (i.e., neoteny), which critically affects learning ecologies and affordances, and as such has likely contributed to shaping the cultural evolution of language . . . First, [it gives] rise to more learning opportunities through culture, imitation, and exposure—as opposed to innate knowledge—which can in turn facilitate the acquisition of more and/or richer signals. Second, and perhaps more importantly, an extended juvenile period is also associated with more (allo)parenting and more explicit teaching behaviours, which directly facilitate language learning . . . In the case of language evolution via HSD, the rise of direct scaffolding of communication by parents and caregivers (e.g. child-directed speech) has been argued to provide children with the possibility to master increasingly semantically complex signals.

* A compressed signal is like ‘4y’ instead of the longer 0.7y + 2y + y + 0.3y. These can be seen as equivalent ‘messages’ communicated with different numbers of ‘bits,’ the former being transmitted with fewer, so it is more ‘efficient’ (depending on the use case). The latter, however, is more ‘informative’ as to the breakdown of the groups and how many there are. Compressibility and informativeness are “partially competing pressures that operate on languages in the process of cultural evolution.”