Give Me a Map, Not a Maze

Why Opportunity, Not Necessity, Drives Innovation

You know, it matters how people frame certain issues, in general, doesn’t it? But perhaps you think it doesn’t matter. And perhaps a plurality of your neighbors or fellow citizens share this belief—this framing—with you. If that were the case, it would have implications, for this imagined group at least, on, say, strategies for consensus-building, disagreement resolution, and coordinated action. That is, if the people in the group do not believe that effective re-framings or different framings should have any effect on their learning or decision making about important issues, then that framing (a framing that is against framing, if you will) would certainly matter—a kind of proof by contradiction that framings are important and that they are thus worth investigating.

It seems intuitively obvious that different experiences and different knowledge among individuals and groups can lead to different framings, but we also have research supporting this intuition. A classic example, Chi, M. T. H., Feltovich, P. J., & Glaser, R. (1981), shows us that novices and experts—two groups who definitionally differ by knowledge and experience—categorize problems within a domain differently (they ‘see’ them differently), with experts sorting problems according to their ‘deep structure’ and novices primarily by their surface features. Another classic, Chase, W. G., & Simon, H. A. (1973), demonstrates that experts can ‘see’ meaning where novices see just noise. Different knowledge and experience within a domain (for Chi, et. al, it’s physics; for Chase and Simon, chess) lead to different ‘views’ of that domain and thus different ways of working within it.

Even when we take care to attend to different knowledge and experience, rather than more or less within a domain, different framings still emerge—and can cause lots of trouble—as a result. In her influential book The Body Multiple, Annemarie Mol demonstrates how patients and healthcare clinicians, including nurses, operate under radically different framings, even when both are competent and informed, attuned to the same concern—the well-being of the patient—and empathetic toward each other. Similar differential framings, along with similar consequences, are well known to adults and can be found between bureaucrats and the citizens they serve, between sports fans and the players, and between lawyers and their clients (not to mention teachers, their students, and their students’ parents).

Importantly, while social role plays a part, the framing differences that travel with roles—teacher vs. parent, doctor vs. patient—are mostly carried by the knowledge and experience people acquire within those roles, not by the role itself. The strength of knowledge and experience over ‘role,’ per se, is why people often find it difficult to take off their teacher hat or lawyer hat, etc., and are just as often surprised to be still wearing it outside of the ‘official’ requirements of their ‘role.’ What matters to our framings, in line with the research above, is that knowledge and experience, expressed through a person’s ‘role,’ have the power to rewire perceptions of situations, reorganize understanding, and facilitate pattern recognition.

Framing ‘Innovation’

If knowledge and experience—rather than ‘role—most strongly influence or even determine one’s framings, then let us honestly consider this somewhat pugnacious question: What specialized knowledge about or experience with ‘innovation’ do teachers have, on average? It is not a difficult question. Nor is it tricky or nuanced. The answer is clearly ‘none’—just like everyone else. This is not to say that teachers are unable to innovate or are unable to spot and intelligently discuss innovations as and when they see them (like everyone else). It is to say, simply and inarguably, that teachers’ intuitions about ‘innovation’ are likely to reflect the same public narratives the rest of us absorb.

Given this broad overlap in knowledge and experience (and thus framings) among teaching staff and ‘laypeople’ around the subject of innovation, how might we describe what this more-or-less shared opinion looks like, in general? How might we describe how most people (in the U.S.) frame innovation?

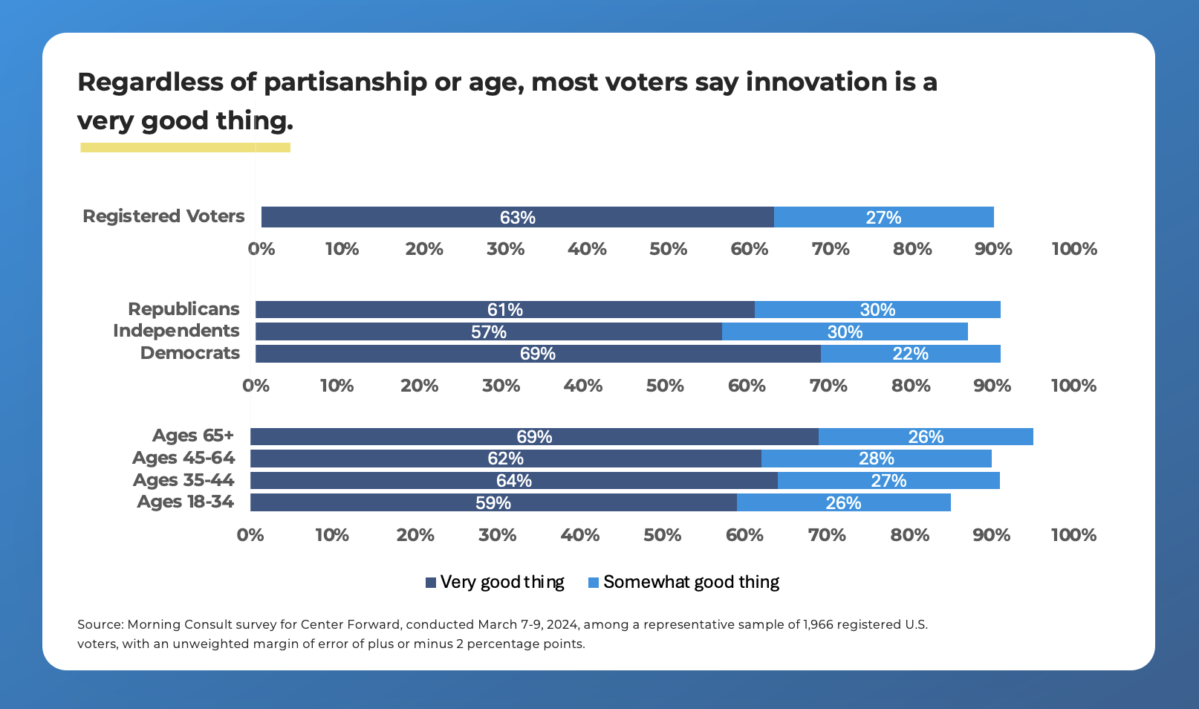

A few strong centers of agreement stand out from recent polling data. (It’s not education-specific, but it does reveal the default cultural narrative most educators and parents swim in before any specialized experience intervenes.) By far the strongest signal from polling indicates that innovation, as a mere concept, enjoys an unusually widespread positive regard (PDF), across political divides and among all age groups.

While this admiration for innovation is tempered by concerns about AI and worries that our abilities to control the progress of innovation remain too limited, it still reflects a longstanding optimistic trend. In 2011, for example, not long after the Great Recession of 2007–2009, 94% of people in one poll said that innovation is somewhat important or very important to the economy.

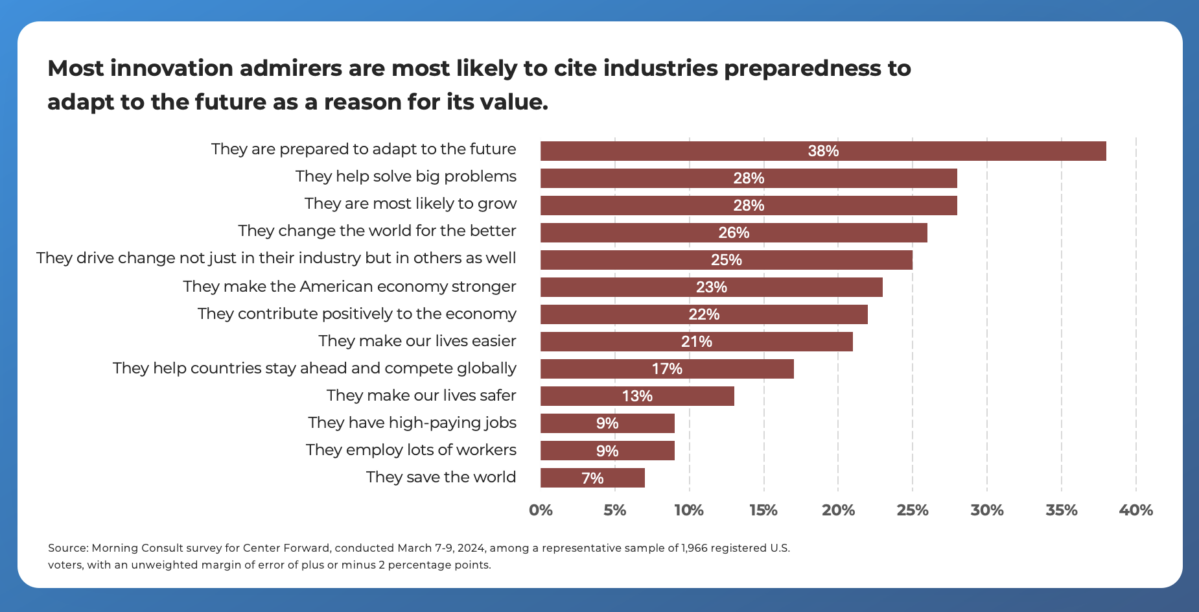

Another area of shared framing speaks to our collective thinking about who it is that is innovative. And the answer is: people who work in—or will work in—technology. In a March 2024 poll (see PDF link above), U.S. voters were asked what industry was best characterized by the term ‘innovative,’ and the technology sector topped the list at 38%, with no other industry even close. (Telecommunications came in second at 10%, and one wonders whether it—in the age of the iPhone—should not be folded into the ‘technology’ category also.)

Finally, in addition to a near-universal love for at least the idea of innovation and a widespread belief that technologists ‘own’ it, people tend to believe that innovation is a problem-solving machine, with solutions lying over the horizon of the present (see PDF link again).

Spears Over Baskets

Notice the meager percents for safety, wages, and employment in the results above. The respondents are not heartless technocrats; they’re just regular people, teachers included, who do not really know much about innovation, don’t think about it all that much or all that deeply, and have little lived experience with it directly. This makes them (all of us) easy prey for biases—and one in particular that I call “spears over baskets,” though it goes by various names. Ursula Le Guin’s 1986 “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction” (PDF) is a short and easy-to-read narrative exposé of this seductive bias:

In the temperate and tropical regions where it appears that hominids evolved into human beings, the principal food of the species was vegetable. Sixty-five to eighty percent of what human beings ate in those regions in Paleolithic, Neolithic, and prehistoric times was gathered; only in the extreme Arctic was meat the staple food. The mammoth hunters spectacularly occupy the cave wall and the mind, but what we actually did to stay alive and fat was gather seeds, roots, sprouts, shoots, leaves, nuts, berries, fruits, and grains, adding bugs and mollusks and netting or snaring birds, fish, rats, rabbits, and other tuskless small fry to up the protein. And we didn’t even work hard at it—much less hard than peasants slaving in somebody else’s field after agriculture was invented, much less hard than paid workers since civilization was invented. The average prehistoric person could make a nice living in about a fifteen-hour work week.

Fifteen hours a week for subsistence leaves a lot of time for other things. So much time that maybe the restless ones who didn’t have a baby around to enliven their life, or skill in making or cooking or singing, or very interesting thoughts to think, decided to slope off and hunt mammoths. The skillful hunters then would come staggering back with a load of meat, a lot of ivory and a story. It wasn’t the meat that made the difference. It was the story.

The spears-over-baskets bias is revealed in our sense that this opening to Le Guin’s essay has already turned the story in our collective memories upside down. In that story, “man as hunter” provides meat from hunting, on which we rely for nearly all of our caloric intake. The cunning to invent the spear and the bow and arrow, along with the labor intensity required to make use of not only the meat but also the hides, bones, and fat of our kills—these things made it possible for us to survive as humans. But in Le Guin’s more accurate scene (although she may overshoot the truth somewhat in the opposite direction) the basket (container) was at least as consequential an innovation as the spear, since gathering was far more consequential to our survival and comfort than was hunting. Yet, we remember the hunting stories, not the gathering stories. It is they that become our collective framing:

It is hard to tell a really gripping tale of how I wrested a wild-oat seed from its husk, and then another, and then another, and then another, and then another, and then I scratched my gnat bites, and Ool said something funny, and we went to the creek and got a drink and watched newts for a while, and then I found another patch of oats . . . No, it does not compare, it cannot compete with how I thrust my spear deep into the titanic hairy flank while Oob, impaled on one huge sweeping tusk, writhed screaming, and blood spouted everywhere in crimson torrents, and Boob was crushed to jelly when the mammoth fell on him as I shot my unerring arrow straight through eye to brain . . . .

I’m not telling that story. We’ve heard it, we’ve all heard all about all the sticks and spears and swords, the things to bash and poke and hit with, the long, hard things, but we have not heard about the thing to put things in, the container for the thing contained. That is a new story. That is news.

Perhaps our polling results reveal that this story, this biased framing, this “force energy outward” rather than “bring energy home,” as Le Guin writes, is still at work in us: innovation is a universally beloved tale of conquest in spite of its risks and inequitable benefits, it is lopsidedly associated with ostentatious technological gadgetry like computers, phones, cars, and planes (durable wood and stone spears over ‘degradable’ plant fibers) and it is born of a conjured necessity, to solve problems—not the real everyday problems of safety and subsistence, but the ‘mammoth’ problems “out there,” in the future (who cares about homelessness when China might land on the Moon?). Without knowledge of alternative stories, we are subject to these showiest and most memorable memes on offer—all of us, teachers included—and they become the framings under which we operate. Indeed, taking our list backward, we can reassemble the modern ‘innovative classroom’: throw problems at students while removing supports, generating a motivating necessity, use showy technology as much as possible, and don’t worry, the benefits—promising to all but accrued by only some—will arrive inevitably, in the future, always just over the horizon.

Research on Innovation

The biases that jump aboard our brains and infect our framings when corrective knowledge and experience are absent provide the reasons for needing scientific research to help guide us—even on issues such as how we should frame the notion of innovation. Scientists, like teachers and everyone else are not endowed solely by the hat they wear with any uniquely admirable sagacity about innovation, and the general processes scientists use to investigate phenomena like innovation are certainly not infallible. But the scientific method—warts and all—has proven time and time again to be one of the best tools we have for weeding out bias and delivering a sharp picture of the reality within which we exist. This does not mean that we get to relax our critical-thinking capacities when science tells us something versus when our neighbor does. Yet, when concepts like innovation remain poorly understood all around, scientific thinking can help us break down and organize ideas, giving us a more manageable view, to start, of the extent and the boundaries of the issues involved. Research in cultural evolution, for example, offers helpful insights into how innovation may work ‘naturally,’ in the wild:

The ‘necessity’ hypothesis advocates that innovation is more likely when resources are scarce, and as such, innovations increase productivity or foraging efficiency . . . the ‘opportunity’ hypothesis proposes that exposure to certain resources or environmental conditions (e.g., encountering fruits in the presence of tool materials) facilitates innovation . . . Finally, the ‘spare time’ hypothesis . . . contends that innovation is facilitated by a lack of distractions or environmental stressors, in line with the idea that slack (i.e. spare or plentiful) resources such as time or capital can promote human innovation.

While these hypotheses are of course not mutually exclusive and almost certainly overlap and interact, ‘necessity’-driven innovation seems to be our default framing. It is the engine behind contemporary pedagogical thinking (biased toward struggle and solving problems), and we even have—around the world, in every culture—some version of the proverb “necessity is the mother of invention,” attributed to Plato. (And, frankly, necessity seems to take up most of the air in cultural-evolution research as well.) But it may suffer from the spears-over-baskets bias. Le Guin’s somewhat fanciful story, on the other hand, would likely find sympathy with the ‘spare time’ hypothesis (“fifteen hours a week for subsistence leaves a lot of time for other things”). So, what about ‘opportunity’-driven innovation? Might there be good reasons for the opportunity hypothesis to be a better, less biased fit for human innovation, as we encounter it naturally?

Give Me a Map, Not a Maze

Necessity causes stress. In primates, it rapidly impairs prefrontal cortex functions that support cognitive flexibility, planning, and trying alternatives. Of course, necessity stresses out birds, fish, and other animals too, but the consequences of stress are different because the cognitive, developmental, and—crucially—social architectures of primates, especially humans, are radically different. In many non-primate animals, innovation is shallow, immediate, and state-dependent: a hungry individual is pushed, by necessity, past neophobia into sampling a risky option, and a workable alternative may be discovered quickly. In primates, however, many of the behaviors classified as ‘innovations’—especially tool use and extractive foraging techniques—are more like skills than they are like reflexes, and often require sustained exploration, repeated failures, and gradual refinement over long developmental periods.

This is where robust primate sociality fundamentally alters the innovation landscape. Primates are unusually effective at converting opportunity into innovation because social relationships provide safety and stress buffering, preserving exploratory bandwidth. Extended development further amplifies this effect. Primate young ones have long learning periods, during which exploration, play, and low-stakes failure are tolerated. Recent work on wild chimpanzees shows that proficient stick-tool use develops over more than a decade. This strongly suggests that primate innovations are rarely one-off solutions to immediate problems; instead, they are behaviors whose emergence depends on time, safety, and repeated engagement. Finally, and most importantly, innovation in primates is tightly entangled with the capacity to observe, copy, and stabilize new behaviors. Socially transmitted innovations persist, spread, and become visible as traditions.

Conclusion

Schools are uniquely powerful, formative institutions within our society. Even in the absence of directly imparting academic knowledge and skills, teaching in schools can help to constitute the framings we take into the world as adults. Without taking this power seriously, though, schools may wind up amplifying the biased framings held by the public at large.

The concept of innovation contains such a biased framing. It is thought, popularly, to be driven by necessity—much like reducing food assistance to needy individuals is thought to incentivize job searching (it doesn’t, in general)—narrowly focused on technology, and optimistically future-oriented, at the expense of the more mundane and everyday needs of the present. When we take the time to investigate knowledge held outside of the bubble of education conferences, education blogs, professional development presentations, education councils, education books, and so on, we might learn that this framing may be doing more harm than good for our children and students.

Children are not birds or fish, who are more often pushed to ‘innovate’ one-off, reflexive solutions to immediate problems under duress. They are sophisticated social creatures with long developmental trajectories and an inheritance of transmissive learning. To stimulate their innovative capacities, it is likely better to provide them with rich opportunities—knowledge, tools, models, time, safety—rather than impose artificial necessities.